In 1854 Charles Dickens wrote: “He likewise entertained his guest, over the soup and fish, with the calculation that he (Bounderby) had eaten in his youth at least three horses under the guise of polonies and saveloys.” (Hard Times. Rev. ed., London, Penguin Books, 2003, p.130.) Kate Flint helpfully provides a note which tells today’s reader: “Polonies are sausages made out of partly cooked meat; saveloys are highly seasoned cooked and dried sausages” (p.315). The inference is that we no longer recognise these names, just as we no longer recognise such words as “ahint” or the geographical reference “Norfolk Island” (Ibid, p.316).

Doubtless them up there in the fabled North (all that existed in Dickens’s time, unless you wanted to send off a convict to the most inaccessible place in the world), wouldn’t recognise this last reference today, no. Down here in the Antipodes there probably isn’t anyone who hasn’t heard of Norfolk Island! And lots of people have been there on holiday—reports varying from lovely, very peaceful, really interesting, to horribly boring, nothing to do. And one or two of us are familiar with the usage “ahint”, so youse lot in yer Oxford and Cambridge Universities can put that in yer pipes and— Er, yes.

But not recognising “polonies and saveloys”? Alas, if only it were so! My memories of the things my grandmother bought that were called polonies or saveloys back in the New Zealand of the 1950s will never leave me. The polonies were bad enough, but the saveloys! If only those travesties of a sausage had been “highly seasoned cooked and dried”. They were white, about 10 to 12 cm long, very, very greasy, and tasted as if they were made entirely of fat eked out with bread. The polonies were different in not being as greasy, tasting faintly of something indefinable rather than just fat, having bright red inedible skins, and a pale fawn rather than whitish interior. Both types required to be boiled.

Nanna used to inflict them on us on the days, fortunately few and far between, when we were fated to have lunch at her place. She lived in South Auckland, in Papatoetoe, and we lived on the North Shore, in Bayswater. This was before the Auckland Harbour Bridge was built, so the journey, in the early days before we had a car, entailed a short bus ride, the Bayswater ferry, a shortish walk to the bus stop, and another, very long bus ride. After my grandfather died Dad inherited the car (eventually: the silly old bat hung onto it for a couple of years, though she didn’t drive): that meant a drive to the Devonport vehicular ferry, crossing the harbour, then the long drive out to her place: the roads were pretty bad and there was no motorway back then. But coming back was much, much worse. We always visited in the weekends, of course, because Dad was at work during the week, and there would be an immense queue for the ferry. It took about half an hour to cross the harbour and ditto to get back. So if a ferry had just gone and you were at the back of the queue, you probably wouldn’t get on the next one, either. Imagine this on a stuffy, humid Auckland afternoon in a car without air-con crammed with tired, disgruntled kids… Ouch.

The Historical Saveloy

The word saveloy comes from the French “cervelat” or “cervelas”. Finding this out did very strange things to my mind: boggling was the least of it. How could those vile white bags of grease be French anything?

Well, obviously poor old Nanna’s weren’t. And it’s pretty clear from the Dickens quote that not all saveloys in the past were beautiful products of la cuisine française, either; bought sausages had a pretty dubious reputation for years in Britain. In this instance the image of horse sausages is being used to bolster up the speaker’s representation of himself as coming from the most deprived and poorest of backgrounds. Dickens has another pejorative reference to the saveloy in Our Mutual Friend, in a scene where Bella Wilfer arrives in a posh carriage to collect her father from his sufficiently humble place of work; she asks him if he’s eaten yet and he is extremely deprecating about having merely “‘partaken of—if one might mention such an article in this superb chariot—of a—Saveloy’”. To which Bella replies: “‘Oh! That’s nothing, Pa!’” Mr Wilfer continues, still deprecatingly:

“‘Truly, it ain’t as much as one could sometimes wish it to be, my dear. … Still, when circumstances over which you have no control, interpose obstacles between yourself and Small Germans, you can’t do better than bring a contented mind to bear on’—again dropping his voice in deference to the chariot—‘Saveloys!’” (Our Mutual Friend, Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1971, p.369-70)

So what was a saveloy supposed to be?

Well, its ancestor was based on a mixture with pork brains, according to Gourmetpedia, where we read that the terms cervelas (French) and Cervelat (German) “derive from cerebrum, the Latin word for brain, in reference to the brain that used to be part of the recipe. The term ‘Cervelat’ is the older of the two. It was first recorded in 1552 by Rabelais, and is derived from zervelada, a Milanese dialect word.

“Zervelada or, in Italian, cervelato, referred to a ‘large, short sausage filled with meat and pork brains’. The contemporary [i.e. modern] recipe is derived from a late nineteenth-century reworking of the traditional recipe that was invented in Basel.”

Possibly the fact that saveloys were originally made from brains explains why Nanna’s unspeakable horrors were white??

Saveloys Today: The Continental Version

The sausage is still extant in Europe but it bears no relation to the greasy things poor Nanna served. The Gourmetpedia article tells us that it “is very popular today in Switzerland”, and is made “roughly of 27% beef, 10% pork, 20% bacon, 15% pork rind and 23% water.” They can be eaten boiled, grilled, or fried.

The sausage is also eaten in France. The recipe “Alsace's Cervelas” on the FRIJE website suggests baking your cervelas wrapped in bacon and stuffed with a generous slice of Emmental cheese. Frankly, even thinking about a combo of cheese and sausage always makes me feel queasy, but maybe in chilly Alsace they need that extra layer of fat around the ribs?

Saveloys Today: The British Legacy

Where are the saveloys of yesteryear? You can find survivors but it’s doubtful if these bear much relation to the traditional saveloy of Dickens’s time and earlier. The Foods of England tells us they are “bright red coloured” and “filled with finely-ground spiced pork”. Their existence has been documented for over 200 years: “Known at least since advertisements by Wall and Garland, Pork Butchers, of 33 Westgate St, Bath, beginning in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette - Thursday 17 October 1793.” (Ibid.)

A typical example of today’s British saveloy (see the picture above) may be found on the UK website, Meats and Sausages: “A saveloy is a type of highly seasoned sausage, usually bright red, normally boiled and frequently available in British fish and chips shops, occasionally also available fried in batter. Although the saveloy was originally made from pork brains, the typical sausage is now made of beef, pork, rusk and spices. The taste of a saveloy is similar to that of a frankfurter… It is usually eaten with chips.”

The butchers’ recipes for making saveloys from this mixture have been published at least since the 1930s: on the sausagemaking.org forum “Parson Snows” gave this recipe:

Saveloy Recipe

“The following is a saveloy recipe copied verbatim from the original Butchers' Book (UK, Circa 1938)”

* 8 lbs Lean Beef, Pork etc. * 2 lbs Pork Fat

* 4 lbs Rusk (soaked) * 1/2 lb liquid smoke powder

Place beef, pork, soaked rusk etc., into machine and chop well, then add seasoning and smoke powder, and colour with Indian Red. Fill into pig skins and boil for 20 minutes in water to which has previously been added one-eighth oz. Bismark Brown, or they may be coloured the same way as Polonies, either with Saupolon or Bismark Brown, or may be hung in the Smoke House to smoke. To soak the Rusk, put the 2 lbs of rusk to 2 quarts of cold water; stir gently round and allow a little time for the rusk to absorb all the water. Some makers also add a little dry rusk whilst chopping the Mixture in Sausage Machine.

Source: Parson Snows. [“Forum”], Franco’s Famous SausageMaking. Org, Thu Nov 11, 2004,

http://forum.sausagemaking.org/viewtopic.php?t=153&sid=063610e4ac0f5d497ac28a7d47f77715

Saveloys Today Downunder

In the Antipodes, the consensus seem to be that today’s saveloys are red. The New Zealand ones look exactly like the English ones—there are innumerable ads for them online; all the supermarkets seem to have them. Would I recommend them? No, I would not, not even these prize-winning ones from New Plymouth!

The Aussies have, or had, a fascinating variation. The term is “battered savs” (fair warning, yep). Across the Tasman the Kiwis describe this abortion as a “hotdog” (I have no idea why: sausage, yes, but nothing like American hotdogs). On the SBS Food website Jane Lawson tells us:

“Although rarely heard of these days, the ‘battered sav’—a saveloy sausage, coated in a yeasted batter and deep-fried—used to feature on every fish and chip shop menu in town, a tradition passed down from our British cousins.

“For me the memory of this munch-as-you-walk, fast-food-on-a-stick, also known as the dagwood dog or pluto pup, is closely linked to the Sydney Royal Easter Show. … It was the one day I would indulge in the battered sav ritual—sadly, the idea of eating one was always so much more pleasant than actually consuming the uniformly greasy and disappointing beast.”

It sounds as if the inside of the Aussie sav, no matter what the colour of the casing, was as revolting as Nanna’s ones, doesn’t it?

Recipes? I have found a New Zealand recipe for a “Golden Saveloy Casserole”, dating, shamingly, from as recently as 2017, but I’ll spare you. It’s soused in a packet soup, so the end result would certainly taste of something, but my reaction was: Do you want to fill your kids with all those chemicals?

The Historical Polony

You’ll find lots of references to polonies in 18th- and 19th-century English sources: not just cookbooks, by no means. The one quoted in the picture above is from Little Buttercup’s song in Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera H.M.S. Pinafore, first produced in 1878. Earlier in the century, after Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1838, the Rev. Barham wrote in Mr. Barney Maguire’s Account of The Coronation (one of his Ingoldsby Legends): “There were cakes and apples in all the chapels, With fine polonies, and rich mellow pears”.

The sausage’s name dates back in English for well over 300 years. In The Foods of England Glyn Hughes writes that the “polony, pelonie, pullony” has been known “at least since ‘The whole Body of Cookery Dissected’ by William Rabisha, 1661”. This was the first edition of this book: successive editions were published (the Library of Congress has digitised its 1673 edition ), but the first is very rare: in 2019 Dominic Winter Auctioneers sold a copy for £5,600, noting: “Rare. Only three UK institutional locations found on Copac (British Library, Bodleian and Leeds University Library), with two other copies traced worldwide on ESTC (Harvard University and University of Chicago).”

Hughes then gives us a very nice recipe from English Housewifry by Elizabeth Moxon, dating from 1764: “To make PULLONY SAUSAGES”: it combines pork or veal leg meat with beef suet, plenty of sage, salt and pepper, concluding: “When you use them [i.e. the mixture], roll them up with as much egg as will make them roll smooth; in rolling them up make them about the length of your fingers, and as thick as two fingers; fry them in butter, which must be boiled before you can put them in, and keep them rolling about in the pan; when they are fried through they are enough.” This tasty recipe is very far removed from the New Zealand polony of the 1950s!

By 1859 the ingredients and methodology are getting closer to the modern type: this is Hughes’s transcription from The English Cookery Book, edited by J.H. Walsh:

Large Smoked Sausages Or Polonies.

347. Season fat and lean pork with some salt, saltpetre, black pepper, and allspice, all in fine powder, and rub into the meat; the sixth day cut it small, and mix with it some shred shalot or garlic, as fine as possible; have ready an ox-gut that has been scoured, salted, and soaked well, and fill it with the above stuffing; tie up the ends, and hang it to smoke as you would hams, but first wrap it in a fold or two of old muslin; it must be high-dried. Some eat it without boiling, but others like it boiled first. The skin should be tied in different places, so as to make each link about eight or nine inches long.

The Development of Modern “Polonies”

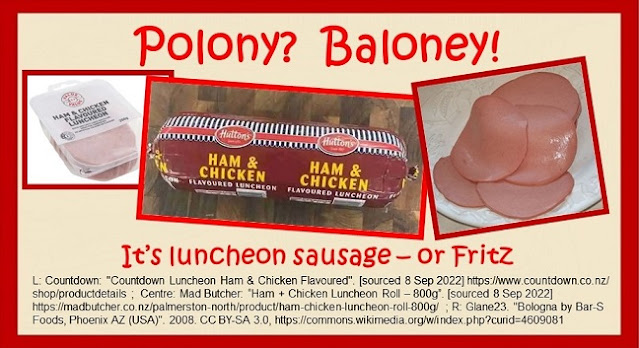

The history of the sausage called “polony” is much more complicated than that of the saveloy. It’s generally agreed, by the dictionaries as well as the food writers, that the word “polony” derives from “Bologna”, the Italian town famous for its sausage, just as the American term “baloney” does. But as the English polony gradually penetrated to the colonies, each place began to use its own recipes—very possibly under the influence of the settlers’ varied ethnic backgrounds—and today the United States has only “bologna”, aka “baloney”, while Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa all have their own versions of “polony”: versions that Dickens and the early sausage makers of England wouldn’t recognise. Bulk manufacturing of course has played its part, too.

In most of the former colonies these “polony” sausages seem to have devolved not into anything resembling Nanna’s polonies, which were plump, red-skinned links about 10 1/2 cm long, in appearance very like those sold today in New Zealand, but into what we always called “luncheon sausage” when I was growing up and which is still widely available today: a stout, very smooth, fairly tasteless giant sausage, bought ready-cooked, often finely sliced, and used in sandwiches. Its casing is generally red plastic. A twin, in fact, of the American boloney.

In South Africa, what we always called “luncheon sausage” is “polony”. It’s long been a favourite. On the website Earthworm Express in his article “The Origins of Polony” (8 March 2019) Eben van Tonder establishes the fact that “polony, bacon, and biltong were made at various sites by 1900” and that “custom built factories for the production of bacon, polony, and biltong” were found all across the country by the 1930s. He examines in depth the relationship between the Americans’ “bologna” and its ancestors, on the one hand, and the local “polony” on the other, and concludes that: “In South Africa, polony became an emulsion only product, … being a natural progression from the more sophisticated bologna recipes… There can be no doubt that it is effectively the same thing.”

Meanwhile on the other side of the Indian Ocean the Western Australians had this large sausage, too, and also called it “polony”, according to the article on Wikipedia under the mystifying title “Devon (sausage)”. The article doesn’t suggest it, but very possibly this has something to do with the relative closeness of South Africa to the western coast of Australia. On the other side of the continent this luncheon sausage can be “Belgium”, “Devon” or even “Windsor”, but in South Australia it's always “Fritz”—originally “Bung Fritz”. I’ve tasted the South Australian one and yep, luncheon sausage is what it is.

Wikipedia, apparently never having compared its photos of the so-called “Devon” and “Bologna” sausages and seen that the two are identical, tells us under “Bologna sausage” (found by searching under “polony”) that: “Bologna sausage, also called baloney (...) or parizer and known in Britain, Ireland, Australia, Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa as polony, is a sausage derived from mortadella, a similar-looking, finely ground pork sausage containing cubes of pork fat, originally from the Italian city of Bologna”.

In New Zealand polonies kept their original name and remained as relatively small, never developing into the big “bologna”, and typically being sold by the string—maybe half a dozen links at a time. Always a cheap food, they retained the somewhat dubious reputation they’d had back in Dickens’s day. Reports such as this one from The Colonist, Volume XLV, Issue 10342, 25 February 1902, didn’t help:

Nevertheless they remained popular, and on 23 December 1929 The New Zealand Herald published a poem called “What I’d Like!” by a 10-year old boy, Robert Baine, in which, after wishing for a pair of “’jamas” with a jacket long enough so that they didn’t come apart at the waist (poor little sprat!), he decided:

I’d like a few polonies,

I’m fond of them, aren’t you?

And as I’m not a greedy chap,

A yard or two would do.

But mince pies and polonies,

As friends are not the best,

And a great big granite tombstone

Might lie heavy on my chest.

And so I think I’ll change my wish,

I’ll not get a chance again,

I’ve a really great big monstrous wish,

For a ’lectric Hornby train.

One with yards and yards of track,

Platforms and tunnels, too.

It seems too much to expect,

But I do wish it would come true.

Robert would have been about four years younger than my dad, who was also a great fan of electric model trains—and remained so all his life. My oldest schoolfriends still recall with a sort of awe his railway layout in the loft of our very ordinary suburban bungalow in Bayswater: only accessible by means of a cunning ladder which he used to haul up and down on a rope. My most vivid memory of the loft is of the awful day on which my little sister, who walked early, so she would scarcely have been a year old, determinedly climbed the ladder in her little white smocked dress and a pair of nappies! The steps were fairly wide and the ladder was very sturdy, but they must have been about 30 cm apart. Poor Dad just about passed out when he caught sight of the tiny almost-bald head appearing up there!

That would have been in the mid-1950s, the era of Nanna’s dreaded sausage lunches. In those days it was still the custom for butchers to make their own polonies and saveloys and their tiny red-skinned cousins, “cheerios” (cocktail sausages). If you were lucky the local butcher in Bayswater would award you a cheerio when you went there with your mum. Goodness only knows why they were such a treat: they were made from the same mixture as the polonies!

The polony carried on: some butchers still make their own, even today, but with the advent of wholesale food manufacturers and supermarkets, mass production is common. The polony’s casing is still bright red, as I mentioned earlier. And these days it appears indistinguishable from its red mate, the soi-disant “saveloy”.

And what are they actually made of? Well, I didn’t set out to track the ingredients: I merely wanted to record a tiny titbit of colonial culinary history before it vanished with those who can remember the 1950s. (As I was researching the topic, the news of Queen Elizabeth II’s death was all over the media: the times, they are a-changing.)

However, I came across a couple of websites that obligingly gave the ingredients, as I was looking for illustrations of the modern products.

Polony: Leonard’s Superior Small Goods Limited (the left-hand photo, above) provides this description of the contents of its “Classic Kiwi Polony Sausages”:

Chicken, Pork, Lamb, Beef, Water, Wheat Flour, Seasoning (Salt, Mineral Salt (451), Antioxidant (316), Spices, Spice Extracts, Preservative (250), Soy Protein

Made in NZ from Local and Imported Ingredients

Saveloy: There was no description of Heller’s saveloys (right-hand photo, above) on the site where I found the best picture, but the Countdown (now Woolworth’s) supermarkets sold the same thing, and their description of “Hellers Saveloys Classic 500g” is:

Meat (70%), Water, Tapioca Starch, Soy Protein, Salt, Mineral Salts (450, 451), Spices and Spice Extract, Vegetable Powders, Flavouring (Smoke Flavour, Emulsifier (433), Acidity Regulator (260)), Antioxidant (316), Preservative (250), Edible Casing1 (Colours (160a, 150c, 160c))

1 Beef

Possibly Polony takes it out by a short nose. They’ve both got, salt, mineral salt, spice extract (the mind boggles, a spice is a spice, surely?), antioxidant, and preservative, along with their soy protein, though.

Depressed? Cheer up. You don’t have to eat them! And as a reward for reading this sad sausage saga, here’s a nice little picture by Walter Crane:

No comments:

Post a Comment